You can listen to this entire blog post as a podcast right here on Newgrounds!

You can also listen, comment & subscribe on SoundCloud

And please find us on iTunes (=

https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/rubberonion-animation-podcast/id730497544?mt=2

#1 – What is “Copyright?”

The actual official definition goes like this…

Copyright is the exclusive and assignable legal right, given to the originator for a fixed number of years, to print, publish, perform, film, or record literary, artistic, or musical material.

A simpler way to think about it is that Copyright gives the creator a monopoly on his/her creation for a certain amount of years, after which it enters the public domain where anyone is free to use it (or copy it) however they want.

Copyright law is even in the U.S. Constitution. Cool.

Right up front, I want to make sure we distinguish between copyright and plagiarism. Plagiarism is when someone steals an idea or expression, and passes it off as their own. You can’t copyright an idea because copyright only applies to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.”

Plagiarism is a matter of ethics. Copyright infringement is law.

The idea of copyright is this…

-

An original creative work is difficult to make (uh huh)

-

It’s difficult to make a living from (with you so far)

-

Creativity is relatively easy steal as most time’s it’s a simple as copying it (ooohhh “copy-right”… I get it now)

So by giving an artist a legal protection from their work being copied, the artist now has a certain amount of time to try and make as much money as (s)he can before it becomes legal for anyone to use/copy/distribute/perform it… because after that time limit, it enters the public domain.

#2 – What is the “Public Domain?”

The public domain is basically any art that isn’t owned. That stuff is free to use for any purpose: reimaginings, remixing or just straight up copying the whole thing. Most of it is just so old they seem like they’ve just always been there – like in the case of some books and music. Film is a different story and I’ll get to that after the bullets but here are some examples of works currently in the public domain.

- Books: The works of Shakespeare, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley and all the Brothers Grimm fairy tales.

- Music: Mozart, Brahms, Bach, Chopin, Mendelssohn (which is why nobody pays for the wedding march song) and Beethoven.

- Film: Wikipedia has a great tally of public domain films like Roger Corman’s Little Shop of Horrors and the Fleisher Superman cartoon serials. There are favorite examples like It’s a Wonderful Life which is actually partially under copyright (the script and the music) which became a Christmas classic almost exclusively because it got a lot of air time on TV since there were no rights to pay. There’s also a particular comedic irony that “Reefer Madness”lapsed into the public domain because of an “improper copyright notice.” Fun.

Public domain is public property and Copyright is private property.

The entire idea behind the public domain is that after a reasonable time where the artist can make money, his/her art should then be free for others to use, copy, alter, and/or build upon it. All creativity is built on something before it so a robust public domain is essential to the progression of creative public expression.

Let’s take, for example, Disney’s first feature length film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. That story by the Brothers Grimm was already in the public domain at the time so Walt Disney was free to use it… and alter it. Let’s not overlook the fact that the story had many alterations to make it more family friendly for the times (and even then, some thought it was too scary for children). The original story was just a jumping off point for Disney. The team still had to build a world, create an entire method for feature length animation production, and get people in the theater to actually see it (Grimm fairy tales had the benefit of having brand recognition before that was probably even a term).

#3 – And then came the United States Copyright Act of 1976

Remember when I said that copyright was protected for a “certain amount of years?” I was being vague up there on purpose. In the United States, that period of time used to be 14 years (which could be renewed for another 14, one time). It is now extended to 70 years after the author’s death. That’s due to many revisions to U.S. Copyright Law. One time in particular, a bunch of revisions happened all at once: that was in 1976. There’s a lot of heat around this Act and I’ll get to that a couple paragraphs down but I want to give a quick example of the types of problems that did actually need fixing.

The distributor of Night of the Living Dead changed the film’s title at the last minute before releasing it in 1968. They failed to include a proper copyright notice in the new titles and in accordance to the law at the time it went immediately into the public domain. File that under “whoops.” That law was revised with the United States Copyright Act of 1976, which allowed a mistake like that to be fixed within five years of publication. If you’re playing along, that’s about 3 years too late for Night of the Living Dead and its fate had been sealed. Which is why I can link the entire movie for you to watch while you read the rest of this article.

It’s more of an excuse to link one of the greatest horror movies ever made in an article on copyright which just happens to have been published in October than an actual cautionary tale, but whatever. I do have a point…

That revision to the law was helpful because it eliminated a silly loophole where the spirit of copyright law was being lost. Not only did is make sure that a mishandled filing could be corrected within 5 years,it also made Copyright automatic when a work is created!

A work is created when it is “fixed” in a copy or phonorecord for the first time.

That’s great! I mean, the last time the law had been addressed before that was in 1909 and there were so many technological advancements which had taken place (radio, TV, movies) that these had to be addressed.

However…

Remember that extension to the “certain amount of time” I mentioned above? To refresh your memory, when copyright was first fixed in the United States the time limit for copyright holders was 28 years (14 year initial term, renewable once). As of 1975, the maximum copyright term was up to 56 years (28 initial, renewable once). Just to bring it down to Earth, pre-“Copyright Act of 1976,” works published in 1958 would have already entered the public domain as of January 1st, 2015. That means films likeVertigo, The Blob (1958), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and books like The Once and Future King, Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s and a bunch more would’ve already been in the public domain! That link is from a page on Duke Law and this quote from it explains the situation of a restricted public domain perfectly:

“Imagine a digital Library of Alexandria containing all of the world’s books from 1958 and earlier, where, thanks to technology, you can search, link, annotate, copy and paste. (Google Books has brought us closer to this reality, but for copyrighted books where there is no separate agreement with the copyright holder, it only shows three short snippets, not the whole book.) You could use these books in your own stories—The Once and Future King was free to draw upon Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (a compilation of King Arthur legends) because Malory’s work was in the public domain. One tale inspires another. That is how the public domain feeds creativity.”

“Consider the variety of films from 1958 that would have become available this year. Fans could share clips with friends or incorporate them into homages… Community theaters could show the full features. Libraries and archivists would be free to digitize and preserve them.”

The Copyright Act of 1976 also defined “work for hire” (see #4) and fair use (see #5). This is where we get into the good stuff.

#4 – “Work for Hire” and the Freelancer

“Work for hire” is mostly talking about employees. If you work at an animation studio and your boss tells you to animate a dancing Hippo, that’s “work for hire” and the boss or the company owns the copyright to the work you produce.

Freelancing is different. As a freelancer, the work done may be considered a work for hire only if all of the following conditions are met:

- the work must be either “a contribution to a collective work, a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, a translation, a supplementary work, a compilation, an instructional text, a test, answer material for a test, or an atlas”

- the work must be specially ordered or commissioned

- there must be a written agreement between the parties specifying that the work is a work made for hire by use of the phrase “work for hire” or “work made for hire.”

So if you have an email or a contract with the words “work for hire” in it… that’s not enough to define it as a legal work for hire and all rights to the work will remain with the creator (you, the freelance artist). Also, the agreement must be negotiated, though not necessarily signed, before the work begins. Retroactive work for hire isn’t allowed.

So what is the client buying then?

The copyright! But not always all of it. I know, it’s circular but stay with me. This get’s a little complicated so I’m going to list out a couple factors below.

-

An original creative work and the copyright to it are separate things.

This means that someone can commission a painting and own the original, but they haven’t bought the copyright. For freelance animators, the agreement is usually to purchase the copyright while you keep the originals.

-

Copyright can be itemized

Copyright to an animated short you create, for instance, can be split up by region, time, media, and even market. That means that you can strike a deal with a client that they get all rights to the HD MOV file you deliver to them for one year and are only to use it for advertising in New York (that’s a media, time, market and regional limit, respectively).

As a freelance animator, you are taking on significant risk going it alone with no guarantee of a stable income or benefits. The reason this works is that you have little to no overhead (that would include the “benefits” mentioned earlier that you don’t have) so your costs of production are lower. Because of that, you can provide more reasonable costs to clients. By itemizing the copyright you are lowering the cost to the client.

For instance, if the client can only pay for a commercial in their local area, they only have to pay you for the copyright to use the animation you created for them as a freelancer in that area (if their budget is super-low, then there are more restrictions like the amount of time they can use it). If their business takes off and they’re ready to expand to other areas, they now need to buy the copyright to use in other regions. By only selling the copyright that is needed for the project, a freelancer can work on much lower budgets while still retaining the opportunity of a more supportive pay-day down the line. And if that pay-day doesn’t come, they still own the rights to use it to promote themselves in the hopes of securing other work. That’s how freelancing works!

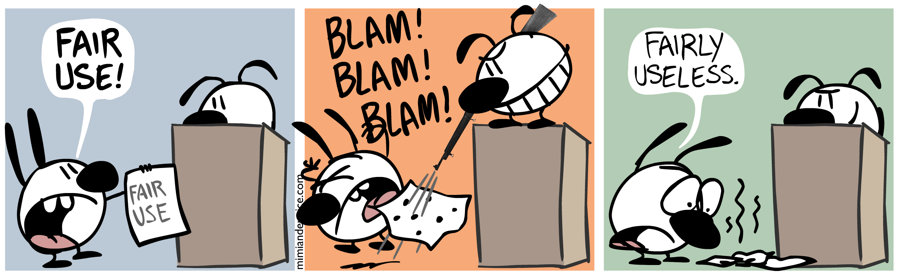

#5 – Fair Use

The common battle cry of the YouTuber: “It’s Fair Use!” Most of the time they probably have no idea what it means so let’s get through some bullet points right away.

-

It’s a doctrine that allows for limited use of copyrighted material without getting permission from the owner

This includes (but isn’t limited to) commentary, criticism, parody, news reporting, research, teaching -

Even if the use of a copyrighted work is covered under fair use, that doesn’t prevent the copyright holder from raising a complaint or suing you

-

Fair use can only be proved in a court, meaning you have to be sued first

Those are the main things to keep in mind. The other thing I want to get out of the way right now is why fair use should even be a thing?

“Much of the unprecedented economic growth of the past ten years can actually be credited to the doctrine of fair use, as the Internet itself depends on the ability to use content in a limited and unlicenced manner.”

~Ed Black, President and CEO of CCIA

So it’s a good thing, in practice… but legally, what constitutes fair use can be tricky. First of all, fair use is a defense you use after you’ve already been taken to court… it doesn’t protect you from that happening in the first place. A judge will determine if fair use is a valid defense on a case by case basis so let’s look at what that decision takes into account.

A judge will determine if it’s fair use by deciding:

-

If you created something new vs just making a copy

-

The amount of the copyrighted material you’re using

-

If your work competes with the original – meaning that it affects the copyright holder’s ability to make money

-

If the resulting work is a criticism, parody or satire

FIRST: Let’s talk about creating vs copying. This is pretty clear but if you’re using the original work as a canvas or building material to make something which stands on its own, that would be creating: like using TMNT toy heads in the creation of a sculpture of Neptune. If you’re using the copyrighted work without any original artistic alterations: like using a YES album cover as the background in a space cartoon you’re making (unless it’s a parody, which I’ll get to in a bit)

SECOND: The amount of the original you use matters. It’s more about quality than quantity meaning that the amount is relative. For example, copying an entire 3 line haiku might be illegal while taking a paragraph from a book might not. There’s also something called de minimis (latin for “minimal things”) which came about in the sampling age of hip hop which is a doctrine (like fair use is a doctrine) which basically says if nobody could tell what the original was, then the use is so small it couldn’t possibly be copyright infringement. Basically it’s just a calculated risk, the more you use of the original the more likely it is to be copyright infringement.

THIRD: The whole point of copyright is to protect the original creator from people taking that work and competing with him/her. It’s all about the money – protecting a creator for a period of time where they can get that cash. If something you do, using any part of their original work, prevents them from making money off the original… that’s copyright infringement. For instance, if a trailer already exists for a film, cutting a new one yourself would basically act as a substitute for the original. However, certain kinds of market harm are OK… which perfectly dovetails intoooooo…

FORTH: A parody or negative review can affect the market value of the original work, and that’s allowed. Copyright alone doesn’t protect an original work against negative criticism. That is to say, if you make a bad movie… people are allowed to say exactly why it’s so bad and that criticism is considered, in itself, an original work. Take Honest Movie Trailers, for example. The resulting work is new and, in this case, a parody of the original… so it would be covered under a fair use defense. For honest criticism to exist, some copyrighted works need to be used it the presentation of that criticism. But what about parody? What about satire? As animators who create cartoon parodies and upload them to YouTube, that’s what you’re really here for right? I know my audience. Well that’s a delicate topic so I’m going to separate it from this section a bit.

(But first an example of parody that we did ourselves!)

#6 – Parody & Satire

What’s the difference between “parody” and “satire”… and does it matter? First, let’s look at the definitions

- Parodies are using a work in order to poke fun at or comment on the work itself.

- Satires are using a work to poke fun at or comment on something else.

The distinction is pretty necessary because while parodies need to use more of a copyrighted work to comment on the work it’s representing, satire is more broad. In the eyes of a court, a “satirist’s ideas are capable of expression without the use of the other particular work.” So here’s the weird thing… many people are worried about using or even referencing copyrighted work in a parody, but parodies are actually more protected by fair use than broad satire is! For instance

-

Parody: You might be able to show Miley Cyrus riding the wrecking ball from Bob the Builder if you’re parodying the seriousness of her song/video with the marketing to young children.

-

Satire: You probably wouldn’t be able to use the song and imagery in a wider satirical visual statement on the music industry as a whole.

Here’s a perfect example from real life. “An author mimicked the style of a Dr. Seuss book while retelling the facts of the O.J. Simpson murder trial in The Cat NOT in the Hat! A Parody by Dr. Juice.The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals determined that the book was a satire, not a parody, because the book did not poke fun at or ridicule Dr. Seuss. Instead, it merely used the Dr. Seuss characters and style to tell the story of the murder. (Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc., 109 F.3d 1394 (9th Cir. 1997).)” –via nolo.com

The thing is, sometimes they overlap. Harry Partridges’ “Saturday Morning Watchmen” is a perfect example of a specific parody which also manages to be a satire on the concept of turning violent source material into kid’s cartoons. Weird Al Yankovic, Mad Magazine, and just about everything Robot Chicken does… they’re mostly parody with some satire thrown in for good measure. Let’s talk about Weird Al actually…

Weird Al Yankovic is known to “get permission” from the original artist before he puts out a parody song. Here’s the thing though, he doesn’t need to do that. What he does is covered under fair use by way of parody. He creates a new song which doesn’t infringe on the copyright holder’s ability to make money on the original… even though Weird Al is selling his parody. Making money on a parody you made of a copyrighted work is completely legal if your use of the original material is covered under fair use.

Which brings me to my last section…

#7 – Fan Art

You want the quick and dirty? Fan art is a copyright violation.

Weirdly, it’s the lack of parody that seems to make most fan art more vulnerable from a legal standpoint. But first let’s clarify what type of stuff we’re talking about. Fan art is a creative work using characters or settings whose copyright is owned by someone else.

Let’s talk about the words derivative and transformative.

-

A derivative work is an “expressive creation that includes major copyright-protected elements of an original, previously created first work.” The original copyright holder generally has the sole right to make derivative works, like translations, cinematic adaptations and musical arrangements.

Examples would be an English language version of Le Petit Prince or a movie version of a book (like Lord of the Rings)

-

A transformative work is not really a “thing” in that the term is used, but legally it’s just a derivative work which has been changed enough to be considered separate from the copyrighted original

Examples range everything from collages, paint-overs, chronologically arranged Grateful Dead posters and even thumbnails in a search engine… so it’s really up to the discretion of whichever judge is deciding.

So basically…

- Comic Con “artist ally” commissions or prints of The Incredible Hulk

- Animated short showing a moving version of a Calvin & Hobbes comic strip

- Fan fiction describing what you think happened between the season 6 final and season 7 premiere of Parks & Recreation

Those would all be derivative works that aren’t transformative enough to be considered creatively new from the original and would fall under copyright infringement. Basically, if someone who didn’t know any better could look at a piece fan art and not know that it wasn’t “official” or “canon,” it’s probably illegal. Fan art can be protected under fair use (refer to the 4 criteria in the “fair use” section to refresh your memory), it just often isn’t.

So why is fan art allowed, then?

The word should probably be “tolerated” because the bottom line is that if a copyright holder isn’t threatened they usually won’t go out of their way to stop something. It’s not in the best interest of that person or company to get litigious over something that many times boils down to free marketing or a continued support of brand recognition.

Here’s a personal example: the fan art that fans of the RubberOnion Animation Podcast do would technically be copyright infringement… but I love it! It strengthens the bond I have with the audience, increases awareness of the show and my business name, and just straight-up looks cool (because you all are fantastic artists with a real sense of personal style). All that benefits me. But what happens when someone starts selling the art? How about if someone makes a fan animation off an audio clip from the podcast like Rob and I do? That becomes an entirely different matter because now that art is competing with my own in the same market (#3 in the considerations list in the “fair use” section above). I might be fine with it. I might not be. How would you feel?

That’s why this issue is so complicated because it’s always a case by case basis. A copyright holder may be totally fine with derivative fan art (like the Harry Potter Lexicon) until it starts to get sold and compete in the same market with the original (like the Harry Potter Lexicon bounded book).

To parody or not to parody? So like I said, a parody of a copyrighted work is more protected under fair use than a faithful and loving homage because it often covers 3 if not 4 of the fair use criteria. And the more you parody and comment on the original work, the more it’s protected with fair use under those terms. But the things which make a parody more likely to be protected under fair use are the same things which will usually upset the copyright holder. That’s the kind of thing that will inspire a copyright holder to order a Cease and Desist (C&D). So you have two choices…

-

Less Protection, Less Likely to Get C&D: Make fan art faithful to the original (which is less protected under fair use) in a loving way and hope that the copyright holder doesn’t get upset

-

More Protection, More Likely to Get C&D: Make a parody which directly comments on the original copyrighted material and be prepared to get a cease & desist order.

And let’s be clear about cease and desist notices… they’re an “and I really mean it” with official letterhead. It’s not a court order. What that letter is saying is that the copyright holder really doesn’t like what you did or how you’re promoting it and wants you to take it down. And if you think what you did is protected under fair use and you don’t comply with their request for you to take it down, they’re willing to let a court decide. That’s what a C&D is. Fight your battles carefully.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright

http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/fair-use/what-is-fair-use/

http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/fair-use-rule-copyright-material-30100.html

http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html

https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2010/05/13/the-messy-world-of-fan-art-and-copyright/

https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/stopping-internet-plagiarism/your-copyrights-online/3-copyright-myths/

TL;DR

“Too long; Didn’t Read”

- All creative work is copyrighted by default.

- “Fair use” is allowed but often hard to prove in court so use at your own risk.

- Risk is usually proportional to the impact your content has on copyright holder (which is why fan art is usually unenforced).

- Parody is well protected under fair use, but again… court.

- Copyright holders cannot order a deletion of an online file without determining whether that posting reflected “fair use” of the copyrighted material.

- A Cease and Desist (C&D) notice is more like an official request. It says “take that down or else” – where the “or else” is suing you.

- If a lawyer responds to a C&D letter, the sender will usually drop the matter… but if they don’t, get ready for court.

Don't forget to check out my new animation made with Rob Yulfo, "What Was Wrong with MAN OF STEEL?" based of a discussion on the podcast right here on Newgrounds!

BakayaroDaWickrayz

this is such a good read, very informative. thank you for packing all of it and shared them to us!

rubberonion

I'm so glad it helped! Thanks for the comment and the follow